Memory is not solely what is remembered, but what is performed. It sometimes transcends the form of narratives and clings to surfaces— to fabric, to ritual, to the weight of an inherited gesture. The memory is dispersed across textures, images and embodied acts. As Pierre Nora observes, memory retreats into lieux de mémoire; sites, symbols, and objects where it condenses. Memory was never rooted exclusively in the linearity of the grand historical timeline in many regional cultures. Instead it flourished in minor forms, fragmented narratives and practices. It carried discontinuities, ruptures and connections in oral traditions and everyday performative acts that resist monumentalisation.

The vernacular forms of memory were often ephemeral and embodied. It always carried a risk of being overwritten by dominant narratives that seek coherence and authority. In a Deleuzo Guattarian sense, memory flourishes as a minor register that embed heterogeneous voices and disturbs the centres. The regional memories gesture towards alternative epistemologies that extend beyond scripted narratives. In these contexts, memory becomes a tactile, visual, and embodied force which remains as a mode of survival, resistance, and re-creation. Hence, it operates outside the temporal logic of the traditional archive. Tracing the memory means to follow what is done, touched, worn, uttered, and repeated. As a Derridian might put it, it is to trace the hauntology of the human experience, a spectral presence of the past that resists closure, lingering in gestures, objects, and practices. In this sense, memory is not a recollection but a haunting that refuses to be resolved into a solid narrative or a stable archive.

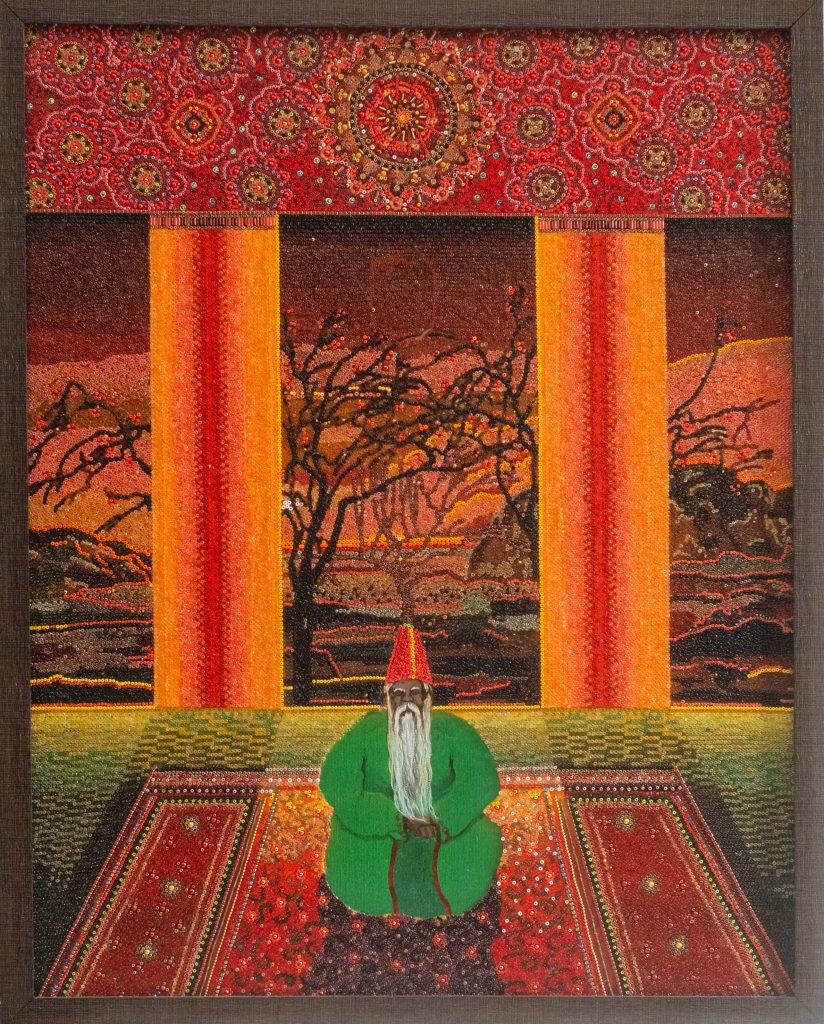

Beads and Textile Colour on Canvas,

16 x 12 Inches

Archive Fever by Jacques Derrida suggests that the desire to archive is irreducible from the impulse to control, systematise, and stabilise meaning. The archive also constitutes a structure of power while attempting to preserve memory through repression and exclusion. However, there are spectral elements within the apparatus of the archive. The resistance to the preservability of the past is pronounced in the uncategorised marginal voices, ephemeral materials, and uninscribed memories. This feverish tension between the impulse to preserve and the inevitability of forgetting becomes evident in the hauntological dimension of the archive. It is within this terrain that the work of art emerges as a site where memory is mobilised, fragmented and reconfigured.

The artwork often engages with rupture, silence, and the irretrievable in mapping a fractured memoryscape. Thus art performs a counter- archival function by giving form to the unarchivable. In this context, art is an embodied sensorium that defies the mainstream paradigms of memory encoding. While Derrida warns that the archive acts as a preservation mechanism that works by exclusion through institutional power, the artists like Amjum Rizve creatively intervene in that tension.

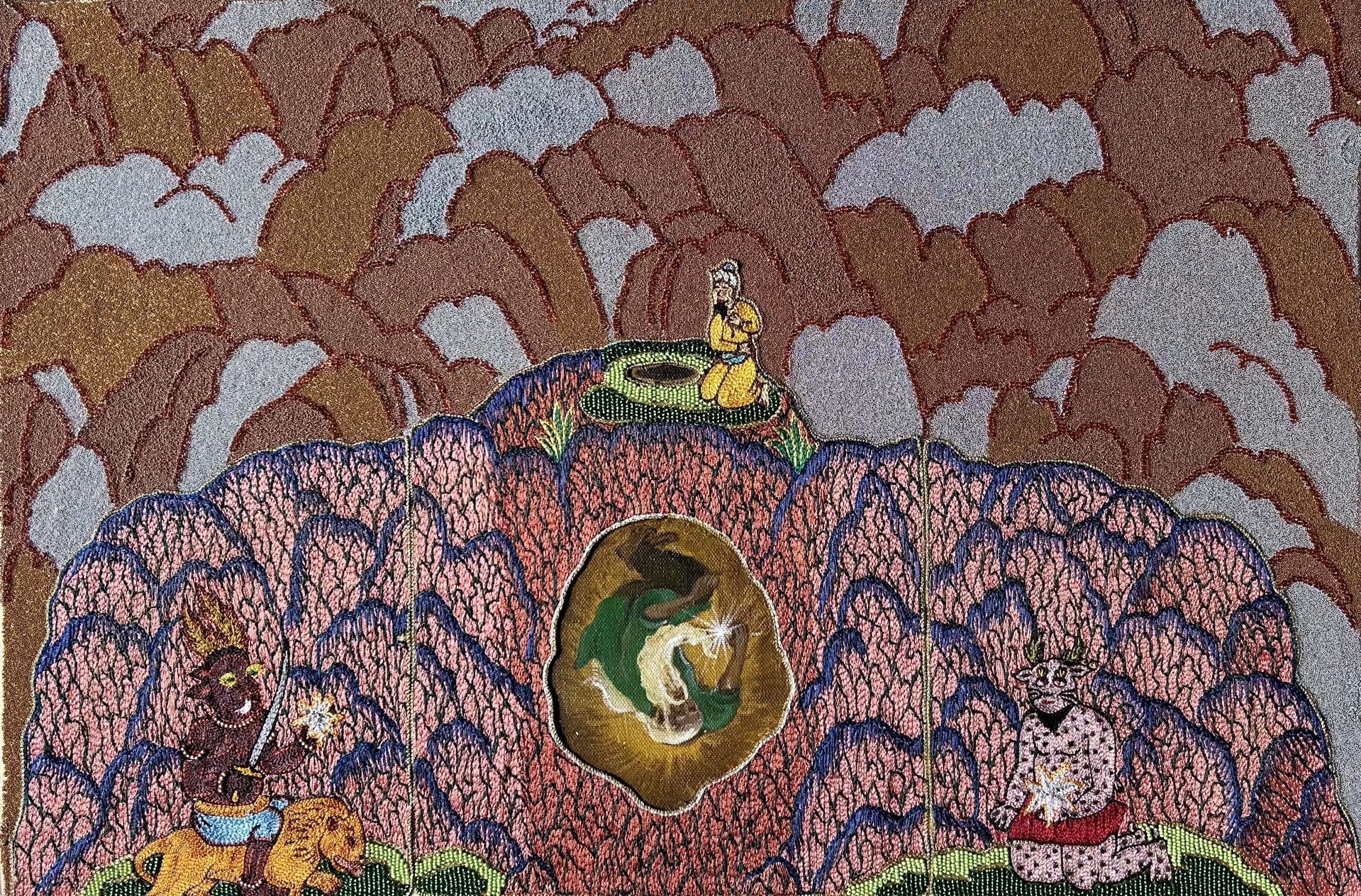

Beads on Canvas,

35 x 45.5 Inches

The works of Rizve perform memory through materials, gestures and sensorial environments. Therefore, he archives the ephemeral, the oral and the tactile that resists inscription. Rizve’s artistic practice is rooted in the cultural and spiritual ecologies of northern Kerala. The works carry the memories that lived through shrines, rituals, and inherited gestures. The local dargahs, kabristans, and kaavus are memory surfaces that carry affective residues of the past. Drawing upon his familial inheritance of textile work and his madrasa training in khatati (calligraphy), visual compositions in his works are often lush, dense, and meticulously worked with embroidery, beadwork, 3D liners, and other embellishing techniques.

Rizve stages a sensuous archive of presence through heterogeneous links with the past. Rather than a decorative exercise, the repeated patterns and beaded textures become a meditative process just as ritual, dhikr, and breathwork. Seeker and His Land, Storyteller and Symbiotic Kiss are works on a sensate terrain that carries not only pigment but touch. The gesture of carefully stitched and sequenced embellishment reflects the meditative quality of repetitive incantations. These tactile compositions perform memory as an affective encounter. These works are not about memory as content, but as sensations that are embedded and performed through surface and material.

His works operate like palimpsests that are overwritten with gestures of devotion and meditation. The works are noted for its intricate beadwork, embroidery, and layered embellishments. His slow and repetitive artistic process recalls the intimacy of bodily labour and memory. The hand of the artist thus performs a choreography of remembering where each stitch and arrangement of bead becomes a tactile invocation. The attention to ornamentation and surface detail invites to revisit the long- dismissed category of decorative labour which is a mode of making often relegated to the margins of art discourse. It is often dismissed as feminine, amateur or functional. The process involved in Rizve’s art unsettles the long held binary between art and craft. The technique plays a central role by becoming an active agent in inscribing human experiences and memories. From this perspective, his work enters into a silent conversation with artists like Varunika Saraf, whose layered surfaces, pigment washes, and needlework evoke the textures of violence, erasure, and dissent.

Beads, Cloth, Embroidery and Mixed Medium on Canvas,

16 x 24 Inches

This correspondence between bodily repetition and memory in the works of Rizve resonates with the oral-formulaic theory put forth by Milman Parry and Albert Lord. Their enquiries about South Slavic epic traditions revealed that memory in oral cultures is not preserved through inscription rather through performance. The oral poet does not recite a fixed text rather improvises within a shared structure by using repetition as a generative act. Memory is dynamic, flexible and sensorial in such paradigms. It moves through breath, voice, and gesture. The artistic process of Rizve echoes this logic since his repeated motifs, meticulous stitching, and layered ornamentations act like visual formulas that are flexible and at the same time structured, expressive yet inherited. Rizve transmits memory and experience through the minor techniques of tactile labour, just as the raconteur inherits and modifies tradition with each telling. Thus, artwork becomes not a record but an event: a performance of memory.

This sensory and mnemonic act is inseparable from the locale. The artistic practice of Rizve is shaped by the vernacular landscapes- the sacred groves (kaavu), dargahs, kabristans, mosques, and paddy fields of Malabar. His works intensifies the regional by holding tradition as a generative and contemporary force. Here the vernacular is a lived epistemology, an embodied sensorium, and a political method. This does not make the practice parochial; instead it is shaped by migrations, sufi lineages and transoceanic circulations that tie Malabar to the Persian Gulf and beyond. Though this visual language is anchored in the local, it constantly communicates with Persian ornamentation and Mughal miniature aesthetics. This porous style creates a transhistorical, and at the same time an intimate, world.

Amalu is a bilingual writer and research scholar at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIST Thiruvananthapuram. Her doctoral research investigates art historiography in Kerala, focusing on the cultural critique of art writing, regional modernity, and visual literacy. She has published on contemporary philosophy and visual culture.