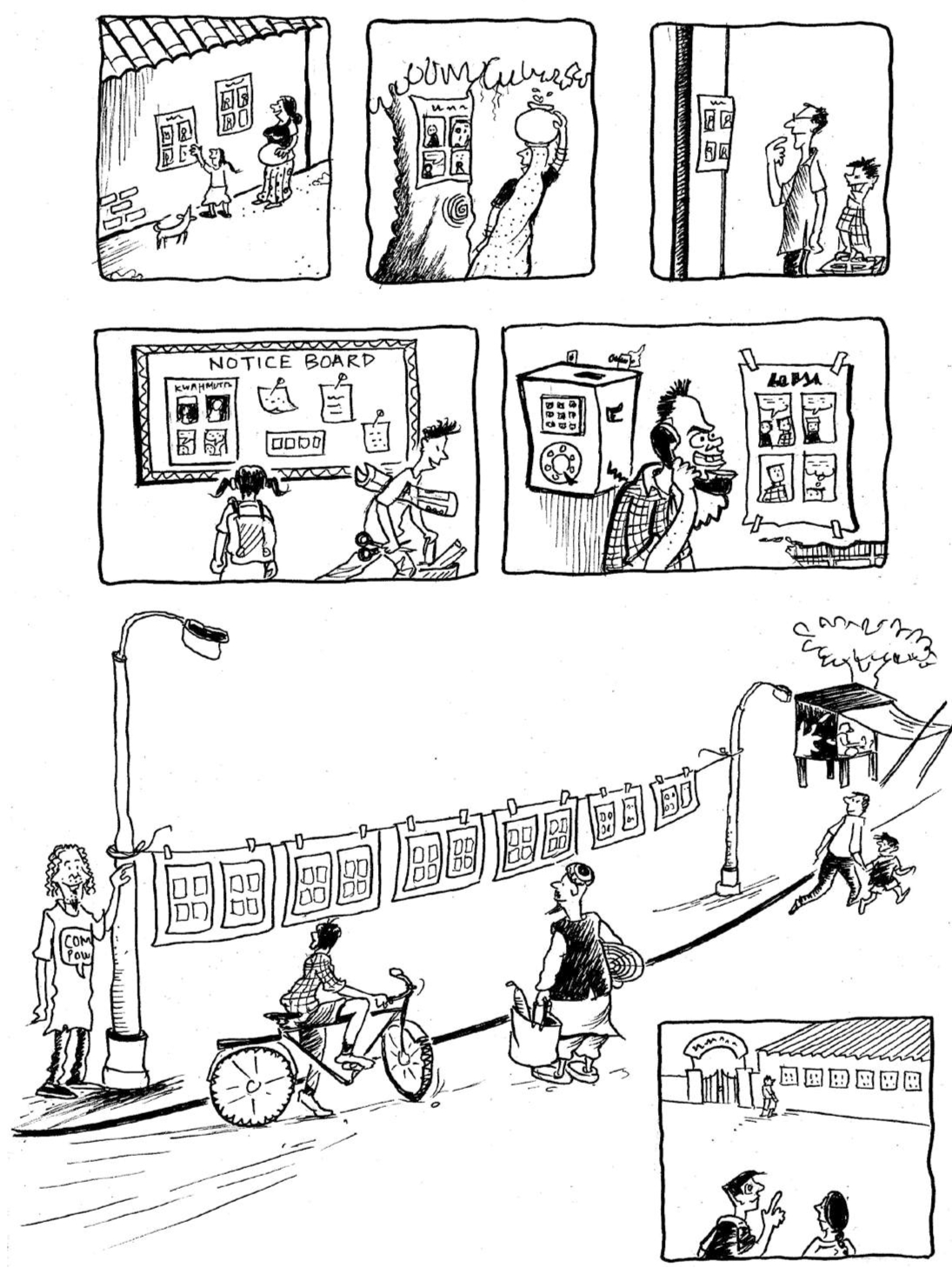

Fig. 1. Scott McCloud. Understanding Comics

When one hears the word ‘comics’, one conventionally relates it to superheroes and fantasy fiction. Author Scott McCloud challenged this in Understanding Comics, saying that the medium was defined too narrowly, when it offers limitless possibilities (fig.1). During the past decades, comics have broken away from narrow definitions to encompass myriad themes and narrative methods. Though it is typically associated with portraying fantasy, the medium is well-suited for representing the plurality of lived experiences. Comics can also depict social or political conflict and its effects on people’s lives, serving as a valuable tool for expression and resistance.

It is to be noted that in any conversation about political comics, the subject of political cartoons invariably comes up. The key difference is that graphic novels and comics are storytelling mediums. Political cartoons can also tell stories, but this is not their primary purpose; they offer a satirical eye into specific events/incidents using limited frames, usually published in a newspaper, periodical, or blog. For the sake of brevity, this article will solely discuss the short history of comics and graphic novels that address socio-political situations in India and the radical aspects of their publishing methods.

Readers often wonder why the terms ‘comics’ and ‘graphic novels’ are separate although their visual form is similar. This demands another discussion on the nuances. But in a rigid distinction, graphic novels are always longer narrative works (like novels) that are mostly not serialized publications, unlike comics which are smaller narratives and often serialized (e.g., Amar Chitra Katha). However, in comics and graphic novel scholarship, skepticism is advised toward generalized divisions, to understand the differences and similarities in context-sensitive ways, since these are versatile mediums that refuse to be contained within strict definitions.

The comic/graphic narrative form comprises panels and strips of spaces in between (called gutters) on the page, that engage playfully with space and time to juxtapose different dimensions, perspectives, and causalities of a story/event. This possibility of juxtaposing multiple viewpoints helps to challenge the idea of history as a linear or straight discourse. So, comics can expose the danger of a single story, filling in the blanks and helping to comprehend the larger historical context, while holding the reader’s attention by being creative and engaging in their narration.

Considering these advantages in their form, graphic novels and comics are known to document conflict and resistance all over the world. Joe Sacco, author of Palestine (1993), Safe Area Goražde (2000), Footnotes in Gaza (2009), etc. coined the term ‘comic journalism’. Artists like Sacco travel to conflict regions, make first-hand observations, and draw graphic narratives from their own experiences, interviews, and research, offering an in-depth personal eye into conflict. Art Spiegelman, Marjane Satrapi, Joe Sacco, etc., have popularized the genre of comic journalism, bringing graphic novels and comics to global readership and research. Indian authors have also created works that depict the turbulent state of Indian politics. Many such comics and graphic novels were made on issues like displacement, migration, elections, the COVID-19 pandemic, imprisonment of protesters under the UAPA, etc.

India has a powerful network for comics at the grassroots level called World Comics India, which mobilizes people’s agency to represent their life experiences. In the late 1990s, Sharad Sharma, a visual journalist, founded this network which promoted work not by professional artists but by the very people who sought the agency to improve their lives. Making such comics served as an effective means of communication between ordinary people and state officials, unearthing local stories and issues. Volunteers have been helping people make comics, and photocopy and paste in public places (fig.2). They also disseminate information relating to health and education through comics. WCI has run campaigns across different states- Rajasthan to Mizoram, Kashmir to Tamil Nadu- on issues ranging from female foeticide to caste segregation in prisons. By 2005, it had chapters in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Nepal. It is still a functioning organization, spread to over 20 countries. They have published Development Comics or DevCom, a series of comic anthologies by several local artists on issues related to social development. Whose Development? (2009) addresses how adivasis are being affected by big development projects in Jharkhand, fishermen’s harsh living situations in Goa, etc., and Parallel Lines: Comics anthology on development (2010) having stories including a daily wage laborer’s life during Commonwealth games 2010, legal victory of farmers over BT cotton in Madhya Pradesh and more.

Fig. 2. World Comics India. Basic Manual

For more than two decades, graphic novels and comics in India have dealt with political themes. River of Stories by Orjit Sen, originally published by the environmental nonprofit organization Kalpavriksh in 1996, is considered the first graphic novel in India with a journalistic intent. It is an account of the environmental, social, and political issues surrounding the construction of Sardar Sarovar Dam over the Narmada River.

The next notable political graphic narrative is Kashmir Pending (2007), on the disputes and strife in the region of Kashmir, by Naseer Ahmed and Saurabh Singh, published by Phantomville (a graphic novel company set up by artist Sarnath Banerjee and Anindya Roy). Delhi Calm by Viswajyothi Ghosh (published by HarperCollins in 2010) re-imagines Delhi in the 1970s amidst some seminal moments in Indian history. Munnu a Boy from Kashmir (2015) by Malik Sajad (Fourth Estate publications) illuminates the conflicted land of Kashmir through a boy’s childhood. Sarnath Banerjee’s graphic novel All Quiet in Vikaspuri (2015) published by HarperCollins, is set in the background of the water crisis in Delhi. These works have addressed and responded to the socio-political tensions of the country in several ways and have become well-known, owing to distribution by popular and international publishers. HarperCollins played a major role in spreading Indian graphic novels globally.

In India, a large body of political comics and graphic novels are by independent publications, as the following:

Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability (2011) on Dr. B.R Ambedkar by Durgabai Vyam and Subhash Vyam, and Gardener on Wasteland (2011) about Jyotiba and Savitribai Phule by Srividya Natarajan and Aparajita Ninan, both by Navayana Publishing. This Side, That Side: Restorying Partition (An Anthology of Graphic Narratives), published by Yoda Press in 2013, offers diverse views on the partition of India. Following the gang rape case in Delhi known as the Nirbhaya case (2012), Zubaan Books released Drawing the Line: Indian Women Fight Back (2015), a collection of graphic narratives written and illustrated by women. Vidyun Sabhaney and Orjit Sen’s First Hand: Graphic Non-Fiction from India (2016), published by Yoda Press addresses trafficking, migration, and other issues. Amar Bari Tomar Bari Naxalbari (2017) by Sumit Kumar (First publisher: Horizon Books) is set in the newly independent India where food production declined, Zamindars controlled the farms, and a tiny village in West Bengal, Naxalbari, initiated an uprising.

Some comic strips are notable in this context, such as Rashtraman and Rashtrayana (2018-present) by Appupen, posted on social media and later published through Brainded India which satirizes the repressive state apparatus. Similarly, Sanitary Panels (2014-present) by Rachita Taneja on social media platforms takes a distinct feminist angle on social justice and politics.

In comic journalism, the term ‘documentary comics’ is defined by theorist Nina Mickwitz as graphic narratives that “share the ambition to mediate actual events and the real world” (2). Many independent and self-published comics produced during the COVID-19 and aftermath years representing political themes adopt a memoir or documentary format. Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Recollection (2020) by Ita Mehrotra, published by Yoda Press, is based on the Muslim women who started the protest against the CAA-NRC-NPR. Release G.N Saibaba (2020) by Lokesh Khodke, published through Bluejackal Publications (co-founded by the artist), derives inspiration from various media accounts of the life, activism, and arrest of Prof. G.N. Saibaba. Khodke’s Ulat-Pulat on a Mission to Free Safoora and Others (2020) features the incarceration of peaceful protestors under the UAPA and urges for their release. Destined to Starve (2020) by Arghya Manna portrays the vulnerability of unorganized sector workers, migrant workers, and artisans during the COVID-19 pandemic. Haq (2021) is a self-published webcomic by Vidyun Sabhaney on women’s role in the farmers’ protests (from 2020-2021) against the government’s oppressive farm laws. Kashmir ki Kahani (2022) by Sumit Kumar published by Toque Content Solutions Pvt. Ltd. offers a satirically illustrated history of Kashmir. A Letter from Bangladesh (2023) by Partha Banik (self-published through Cross-Cat Comics), is a fictional remembrance of the 1971 liberation war in Bangladesh. These narratives perform a journalistic function with experience-based narration, attention to detail, perspectives, and stylistic aspects of documentary form, differing from mainstream media representations. Some employ fictional or subjective entry points that do not weaken the reality. Comics scholar Hillary Chute writes, “Comics narrative suggests that accuracy is not the opposite of creative invention” (2).

The mode of representation of dissent is directly connected to the method of publication. Independent or self-published comics can be a radical act, having direct, unapologetic perspectives accounting for individual stories and voices, compared to those produced under a corporate method. Their politics rise strongly resilient against the oppressive regime, in the absence of corporate control over readership, and publishing without censorship from authorities.

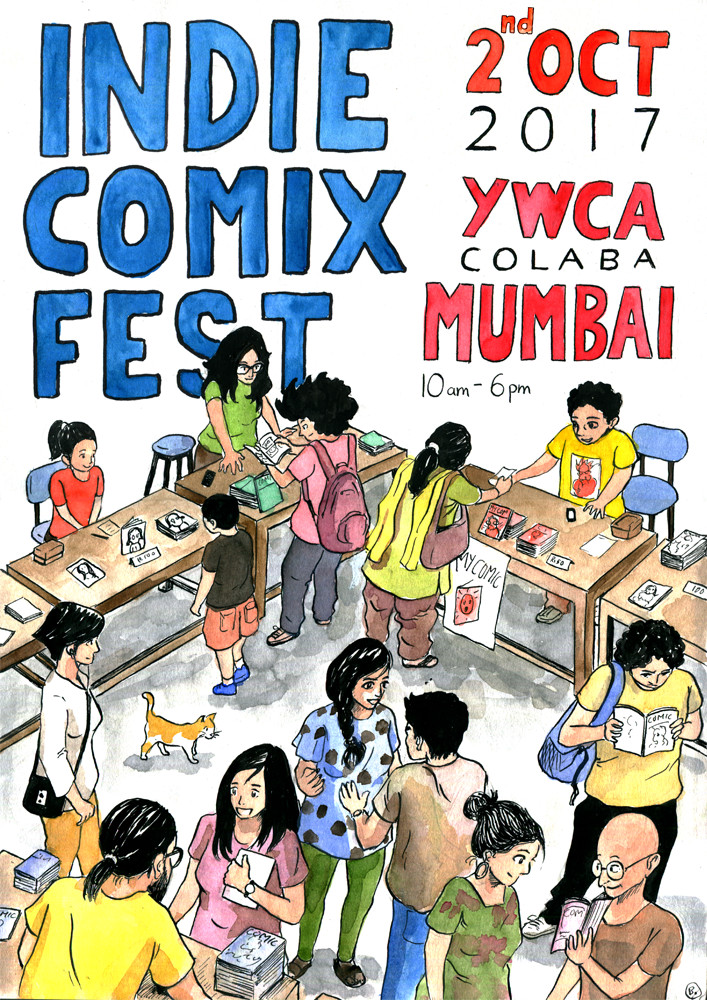

Fig.3. Poster of Indie Comix Fest, Mumbai, 2017

Comics have the power to shape public discourse and rally for social change. Distribution plays a major role in spreading awareness and mobilizing change. Therefore, reaching a wider audience is essential. With the rise of Indie Comix Fest (ICF), which started in Mumbai in 2017 and in subsequent years in Delhi, Bangalore, Kochi, Chennai, Ahmedabad, and Kozhikode, independently published comics have found a public platform. These events offer free entry and affordable comics compared to extravagant Comic Cons. Yet, the information that such festivals exist only reaches a niche audience. The barriers to access and the digital divide hinder their reach to rural audiences and those with limited access to technology. These challenges in distribution and access could be improved through better support and promotion from political organizations, activists, artist communities, or art institutions. Furthermore, traditional and mainstream publishers could also take the responsibility to be more inclusive towards direct representations of unconventional and political subject matter, as these voices of resistance must be heard despite possible backlash from the government.

Works Cited

Chute, Hillary L. Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016.

Mickwitz, Nina. Documentary Comics. 1 ed., Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2016

Image references

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. William Morrow, HarperCollins Publishers, 2018.

Basic Manual. World Comics India,

https://www.worldcomicsindia.com/Manuals/BASIC_MANUAL_Eng.pdf

“Poster of Indie Comix Fest Mumbai 2017.” Indie Comix Fest, 12 Sept. 2017,

indiecomixfest.wordpress.com/2017/09/

Ashlin Sara Paul is an art practitioner and independent researcher, whose creative journey is in the interconnection of literature and art, through mediums like graphic narratives and comics, zines, cut-up texts, and interdisciplinary studies. Their work is centered on comic journalism, queer representation in graphic narratives, and the history of Indian comics. Ashlin completed their MFA in History of Art from Kala Bhavana, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan (2022- 2024), and their MA in English from The English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU), Hyderabad (2019-2021). Currently, Ashlin is a Project Coordinator of Explorations (Art Practice), a Foundation Project implemented by India Foundation for the Arts (IFA), which involves experiments in the making of a graphic narrative in mixed-media book form by collecting women and queer individuals’ personal experiences of gender biases in healthcare, accessibility to public toilets, and the social stigmas surrounding it.

They are one of the recipients of Kerala Lalitakala Akademi’s Scholarship for Art Students (2024), co-curated the group exhibition “Nakshi: Eclectic Realms of Creation”, at Academy of Fine Arts, Kolkata (2024), participated and exhibited their zine in TEXTXET workshop held at Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art (FICA), New Delhi in 2023. They also work as a book illustrator, having illustrated several books such as Thulir’s Stroll (2024), Guardians of the Forest (2023), Myth of the Wild Gaur (2022), After Hours (2022), Eye Am in Denial (2021) and Nimishaardhangal (2019).